What links an imaginary world of toy kings and queens made up by childhood friends in the early 20th century and the real life Queen Mary? Join Museum of Childhood curator Susan Gardner to explore the imaginary realm of Dollyland and the artist that provides the link to Royalty.

A dolls' house fit for a queen

Queen Mary’s dolls’ house, displayed at Windsor Castle, celebrated its 100th anniversary in 2024. It is described as 'the largest and most famous dolls’ house in the world, created by the finest craftspeople, artists and manufacturers of the early 20th century'. Over 700 artists were commissioned to donate a miniature artwork to the dolls’ house and one of these was Elisabeth Brockbank (1882-1949), a member of the Royal Miniature Painters Society. Recent research has revealed that some of the earliest examples of Elisabeth’s work are in the Museum of Childhood collection, unknown to the rest of the art world.

The Realm of Dollyland

Elisabeth Brockbank's artworks form one of the treasures of the Museum of Childhood – a collection of tiny items relating to the imaginary realm of Dollyland. The collection includes handwritten magazines with beautiful illustrations, watercolour paintings and pencil drawings, handmade books and timetables for an imaginary school and a photograph album – all in miniature.

Elisabeth Brockbank, Professional Artist

The Dollyland collection was donated to the Museum of Childhood in 1965 by Margaret Knight. The items were part of an elaborate pastime, created by Margaret and her friend, Marie Elisabeth Brockbank, between about 1899 and 1905. The collection reveals an imaginary world that weaves toys owned by the girls with family life, and a 'realm' that links to the girls' houses and gardens. Fascinating in their own right, the Dollyland items took on a new significance with the discovery that [Marie] Elisabeth Brockbank became a professional artist. She exhibited in many British galleries including the Royal Academy in London and the Royal Scottish Academy in Edinburgh and was elected as a member of the Royal Miniature Painters Society in 1918.

An Imaginary World

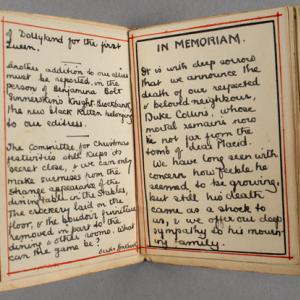

No information was recorded about the origin of Dollyland when it was donated to the museum. The pictures and articles in the magazines are signed with a variety of names which relate to the imaginary world created by Margaret and Elisabeth, although some are signed ‘M.E.B’. The discovery of Margaret Knight on the 1901 Census, which showed that the Brockbank family were her next-door neighbours, provided the breakthrough.

In 1901, Margaret Knight was 11 years old and Elisabeth Brockbank was 18. They lived in Bush Hill, Edmonton, Middlesex. Margaret’s father, Thomas, was a stock agent and Elisabeth’s father was a grocer, druggist and draper. It was a typical middle-class background. The Knight family had a general domestic servant while the Brockbanks employed a cook and housemaid.

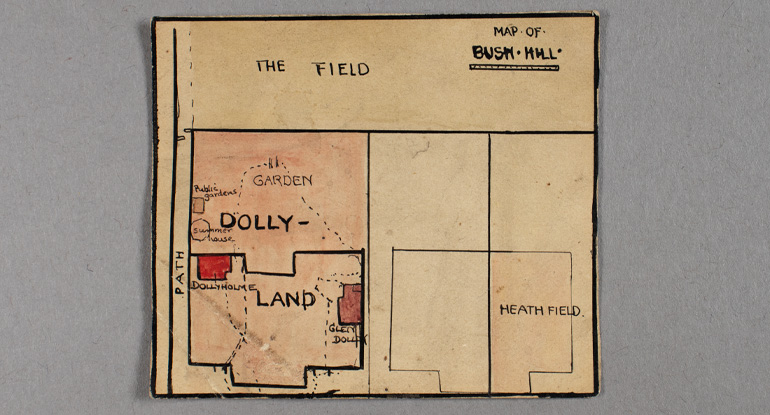

Together, Margaret and Elisabeth invented an imaginary world called Dollyland, occupied by a group of boys and girls inspired by dolls belonging to one or both of them. The dolls can be seen in a tiny photograph album which also gives us a tantalising glimpse of Margaret and Elisabeth and some of their relatives. A miniature watercolour map of Dollyland shows the location of Dollyholme (Margaret’s house) and Glen Dolly (Elisabeth’s house) within the borders of Dollyland.

Royal Dollyland

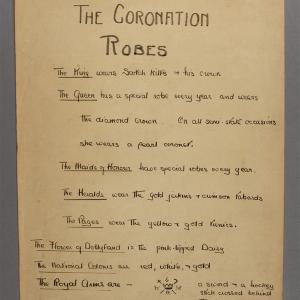

Dollyland is ruled over by an elected king and queen, King William I of the House of Brockbank and Queen Margaret Phyllis (or Marnie) of the House of Knight. Each miniature magazine has a Court News section at the front which describes the activities of the king and queen, including their wedding and coronation. There are also handwritten notices describing the coronation robes, the Laws of the Realm of Dollyland, an Official Book of Ceremonies and a list of the Officers of the Government of Dollyland. The national colours are red, white and gold and the Royal Arms are formed of a sword and hockey stick crossed behind a crown. The Flower of Dollyland is the pink-tipped daisy – a reference to Margaret? (Daisy is often used as a nickname for Margaret.) It’s not unusual to create an imaginary world with a monarchy but it’s tempting to suggest that Margaret and Elisabeth were inspired by the preparations for the coronation of King Edward II, planned to take place in June 1901, and postponed until August due to the King’s illness.

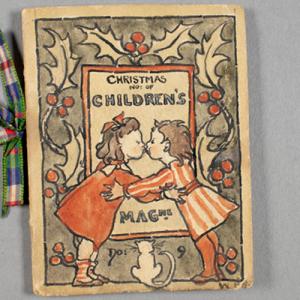

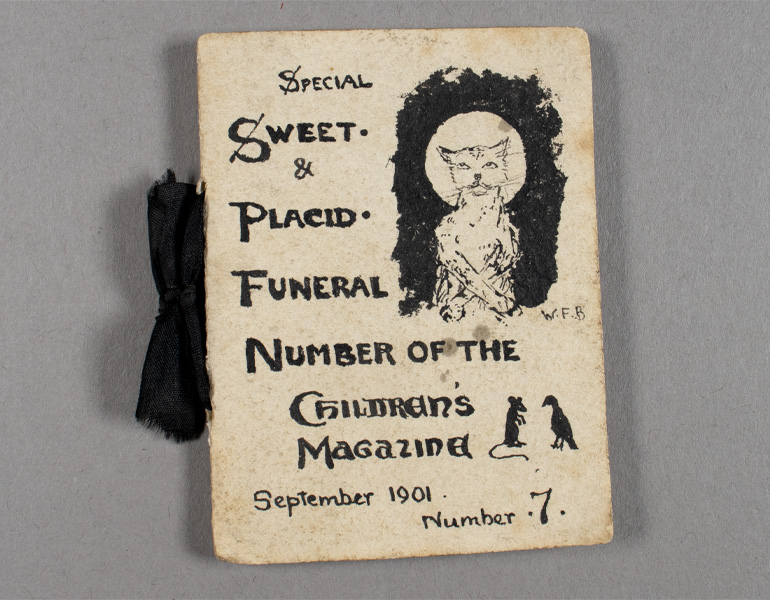

Making home-made magazines was a popular hobby for children at this time and usually followed a standard magazine format of stories, poems, drawings and competitions. The Dollyland magazines include all of these elements but also tell the story of their imaginary characters. The Christmas editions show the children decorating the house, opening presents and eating a special Christmas meal while other activities throughout the year are revealed in the Court News sections.

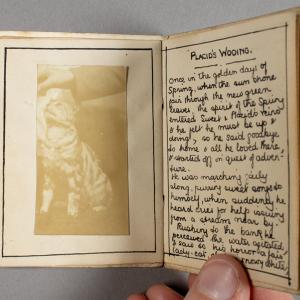

The whole of Dollyland magazine Volume 7 is dedicated to Sweet & Placid, a cat belonging to one of the girls, who has died after getting into a fight, and the death of Duke, a neighbour’s dog, is remembered too. Magazine No.11 records that “two of our number have now been presented with Kodak cameras”. Perhaps these were used to take the photographs in the miniature album? It’s not clear if the magazines were circulated to a group of readers or whether anyone else helped to create them. The articles and drawings are credited with various names which may be variations of Margaret and Elisabeth’s names or may be the names of the imaginary children.

Dollyland's creators grow up

Most of the writing and drawing in the magazines seems to be the work of Elisabeth, rather than Margaret, along with several other watercolour paintings and pencil drawings of the ‘children’. In the 1901 Census she does not have a recorded occupation but perhaps she was preparing to go to art college? Ten years later, in 1911, her occupation is confirmed as ‘painter’. So far, little information about Margaret’s adult life is known, except that she and Elisabeth must have remained lifelong friends. When Elisabeth died in 1949, Margaret was one of two people who inherited her estate, and it seems she spent some of that inheritance travelling to Hong King as a missionary.

Margaret Knight lived until the age of 85. It’s wonderful that she kept the Dollyland items all that time and donated them to the Museum of Childhood. They obviously meant a great deal to her. Still in the spirit of the game, she wrote to the museum’s curator in 1965, “It is a great pleasure to know that ‘Dollyholme’ has arrived safely and that ‘King William and his court’ have received honourable and appreciative welcome!”

Elisabeth Brockbank deserves to be remembered as a talented artist and it’s fitting to highlight her work around the centenary year of Queen Mary’s dolls’ house. For us at the Museum of Childhood, it’s even more exciting to have re-discovered the story behind Elisabeth’s early work, her friendship with Margaret Knight and their joint enterprise – the Realm of Dollyland.