In this blog, Lyn Stevens, curator at the Museum of Childhood explores the origins of a much loved Edinburgh institution, the Royal Hospital for Sick Children which recently moved to a new location.

A little book and a little bear in the Museum of Childhood collection span a history of over 100 years in the story of medical care provided for children in the city of Edinburgh. Edinburgh was one of the first cities in the world to have a hospital dedicated to children and to study the illnesses of childhood as a separate discipline.

Edinburgh’s Royal Hospital for Sick Children, known locally as ‘The Sick Kids’, began life in 1859 as a campaign for a children’s hospital launched by Dr John Smith who published an open letter in ‘The Scotsman’ newspaper. The letter described the suffering of the children amongst the poorest classes - ‘the whisperings of distress lisped out by those unfortunate little creatures are too feeble to attract attention’ read the emotional plea, ‘we must not shut our eyes’ to this situation.

By the following year a children’s hospital in Edinburgh was established in a house in Lauriston Lane with 20 beds. A royal charter was granted in 1863, and after several moves to various locations, the Sick Children’s Hospital was officially opened on 31 October 1895.

The report of the hospital’s first year stated ‘154 children of ages 1 year to 12 years admitted and treated, of whom 140 have been cured and restored to their parents and friends. In the dispensary attached to the hospital 985 children have during the same short period, received medicine – and when necessary they have been visited at their parent’s dwellings and a truly great amount of disease and suffering has thus also been relieved’.

At the time of the hospital being first established the Edinburgh Old Town was a filthy and poverty-stricken slum. There was no sanitation and stinking sewage was everywhere. The death rate of children under 5 was one in 13.

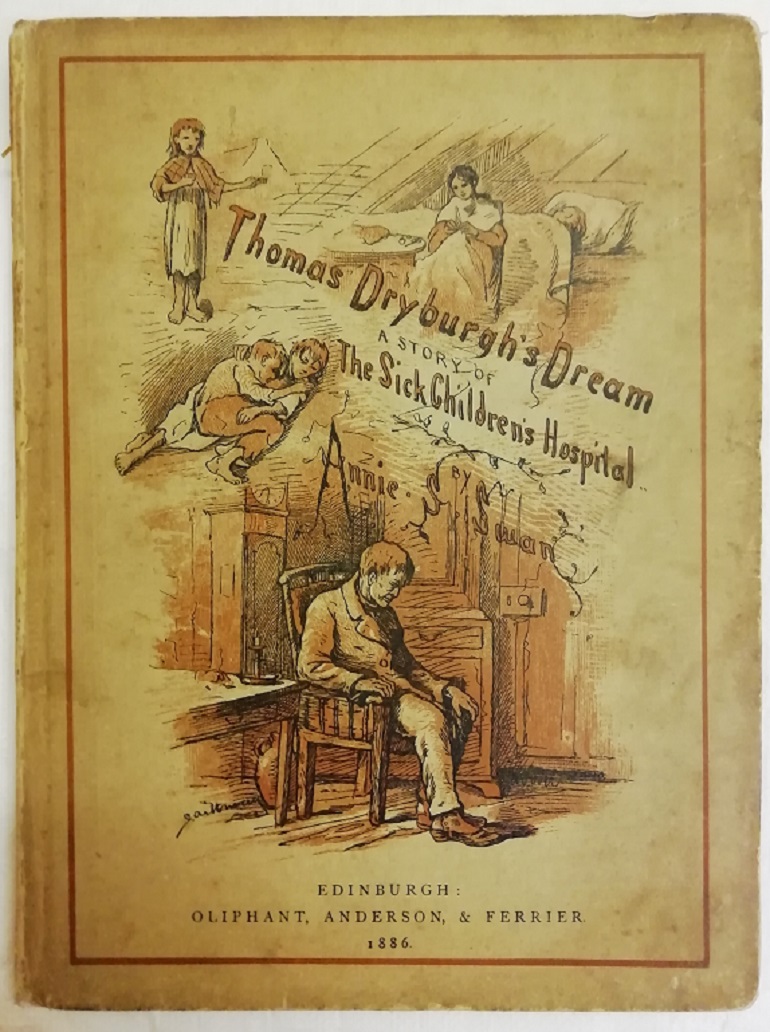

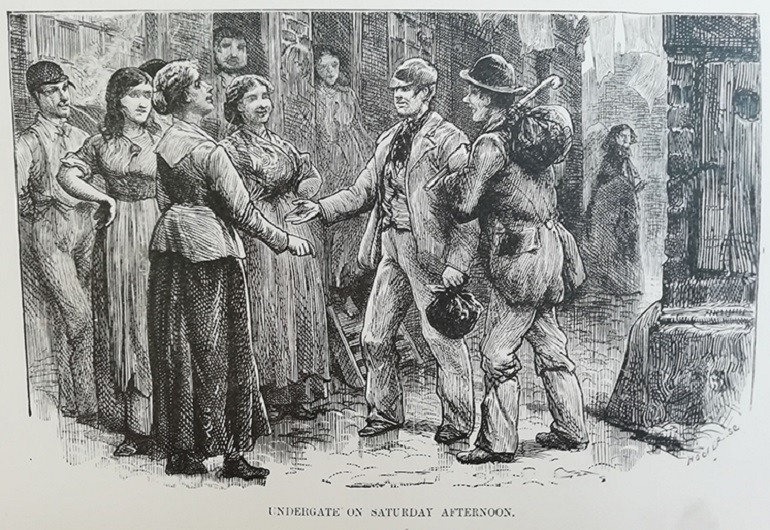

When Annie S Swan’s book ‘Thomas Dryburgh’s Dream A Story of the Sick Children’s Hospital' was published in 1886 the Old Town was still the home of the poorest of the city and the conditions had barely improved. In the book Swan describes the fictional city of Dunleith (Edinburgh) and the poor area of Undergate (Cowgate) where the heroines of the story live. Mary Derrick is a widow with a young daughter trying to earn a living in the big city by sewing. Swan is careful to paint Mary as respectable in her poverty, she hasn’t fallen into prostitution or drink, but she is doing the best she can. However, as her child is sick from malnutrition and damp living conditions, her best is not enough to keep her child healthy.

Mary had come from a picturesque farm in the country where her brother still lived and had moved to the city when she married. Her husband’s death had meant poverty for Mary and her daughter and her brother was unwilling to help as he felt her fate was what she had deserved for going off to get married and leaving him to run the farm on his own. Her brother, Thomas Dryburgh, has a dream where he floats over the city and sees the poverty of the poor children shivering in doorways with bare feet. The dream results in a Dickensian like change of heart (think of Scrooge in ‘A Christmas Carol’), and he comes to the city on Christmas Eve to rescue Mary and donates money to the children’s hospital where his niece is being nursed back to health.

The book ends with a happy scene of the Thomas, Mary and the child back on the farm in healthy surroundings, and a view of Thomas’s bureau, where his will is kept, leaving a legacy for the children’s hospital upon his death. The book is a plea for donations to the children’s hospital.

The author Annie S Swan lived in Morningside in Edinburgh in the 1880s and in addition to the Royal Hospital for Sick Children (Sick Kids) a new Bruntsfield Hospital for women and children had opened the year before Swan’s book was published. The new dispensary for women and children was established by Dr Sophia Jex-Blake, the first woman to practise medicine in Scotland, and one of the ‘Edinburgh Seven’, the first women to be allowed to study medicine at the University of Edinburgh. This hospital was later to amalgamate with the Hospice set up by Elsie Inglis on the High Street, and the two together became the Elsie Inglis Maternity Hospital at Abbeyhill. It is likely Swan would have been aware of all of these efforts to provide better healthcare for the poor children of the city.

Jump ahead over a 100 years and a teddy bear was made to support a 1991 fundraising campaign for a new wing at the Sick Kids hospital. The bear in the collection is named ‘Jamie’ and he was donated by one of the fundraisers for the new wing. The target for the fundraising was £10 million, a figure probably inconceivable to the hospital fundraisers in the nineteenth century. However, this campaign demonstrates that charitable donations to the hospital are not a thing of the past. The campaign was successful, and the new three storey wing was opened in 1995. Still fundraising, the Edinburgh Children’s Hospital Charity supports the work of the hospital to ensure that the children who go there have the best experience possible. The charity is currently running a Covid-19 emergency appeal and continues to fundraise for the Hospital. Read the What we do page on their website.

In 2021 the hospital is about to move into a new £150 million building at a new location at Little France adjoining the Royal Infirmary Hospital. A little bear and a little book illustrate the provision of health care for children from the nineteenth to twentieth centuries, something which has always been supported by the people of Edinburgh.

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

Keep an eye on our events page to book your place at our upcoming, free Auld Reekie Retold digital talks and events. You can find out more about Auld Reekie Retold and read more blogs on the Stories section.

You can find out more about Auld Reekie Retold object discoveries from our Museum Collections Centre on the Capital Collections website.

Further reading ; read more about the history of the Royal Hospital for Sick Children on the Our History section of their website