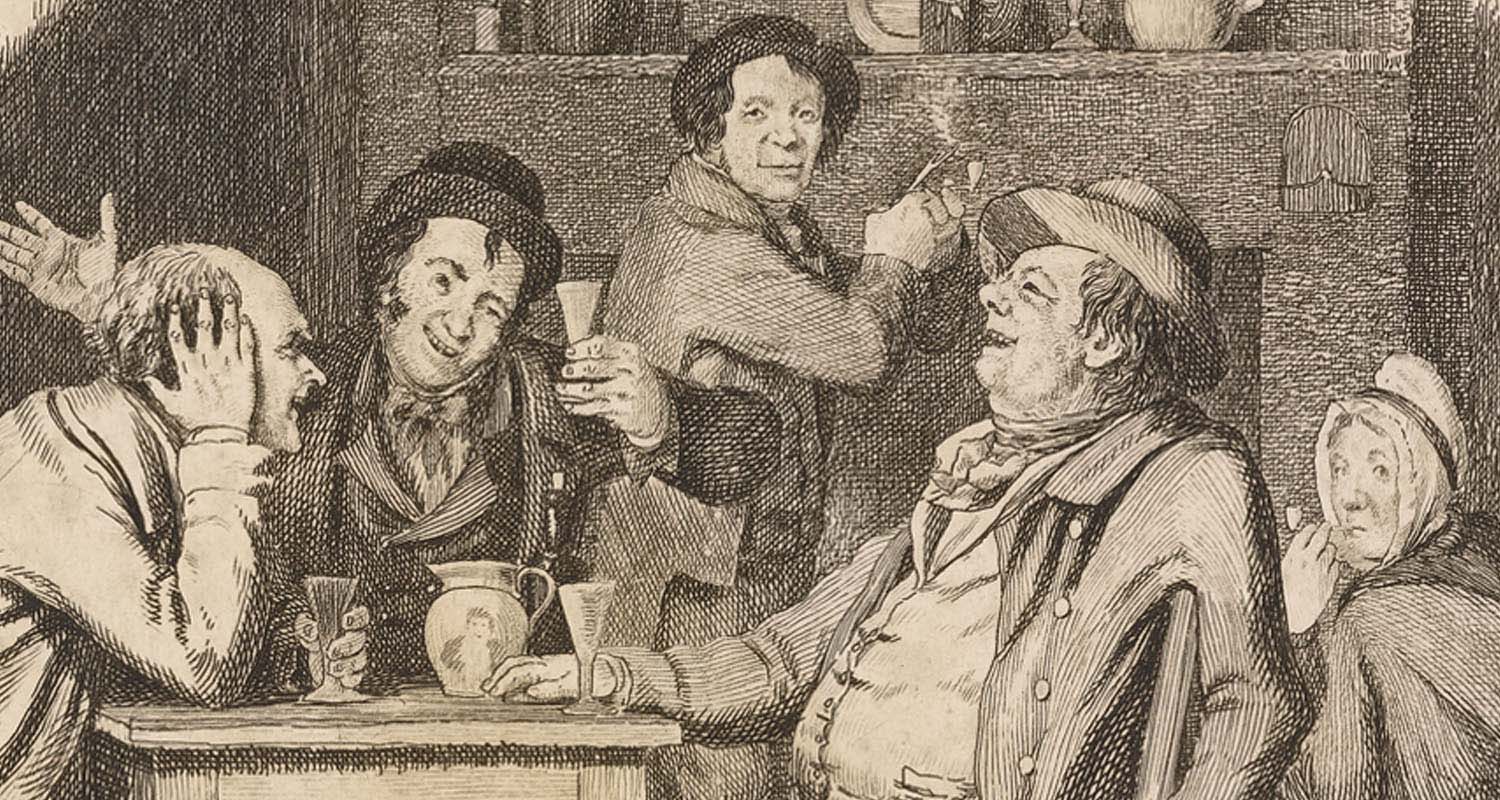

Have you ever wondered what pubs were like in Edinburgh’s Old Town? Or asked yourself what people ate and drank during the 18th century? In this blog, Collections Information Officer Nico Tyack looks at some surprising documents in Museums & Galleries Edinburgh collections which bring the bustling social scene of 18th century Edinburgh to life.

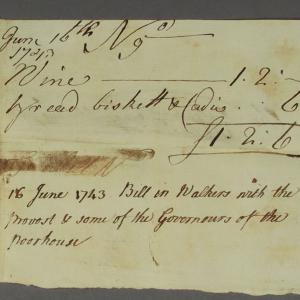

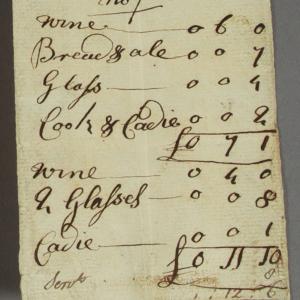

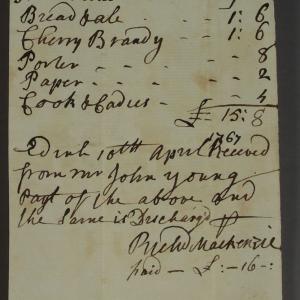

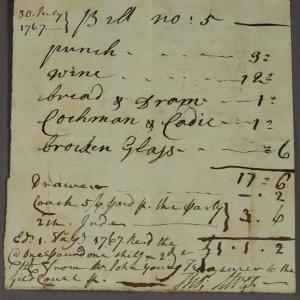

A number of handwritten paper bills from taverns across Edinburgh give a unique insight into the social and gastronomic life of the middle classes. There are 24 bills in the group, dating from 1743 to 1769. The bills reveal some surprising foods, but also show how little has really changed. The décor and menu of the modern pub may have had a few make-overs since the 1700s, but we all still have our favourite haunts, our drink of choice and our chosen pub friends just as they did back then.

Where were the taverns?

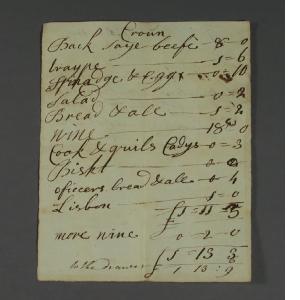

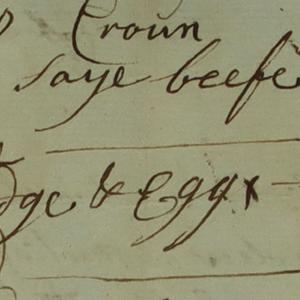

The tavern bills in our collection are all written by hand on scraps of paper. They list all sorts of food, drink and services that people could get at the taverns. Only one tavern has a name we’d recognise as a pub today - the 'Crown'. Most were simply known by the name of the landlord or landlady - 'Richard Mackenzie's' tavern, 'Lawson’s', 'Wilson’s'. We know of the whereabouts of one tavern for certain, 'Mrs Lennose's tavern in Leith', but can only guess where the others were. Edinburgh at this time was still very small, and apart from the busy port of Leith, the city was largely limited to the wynds and closes of the Old Town.

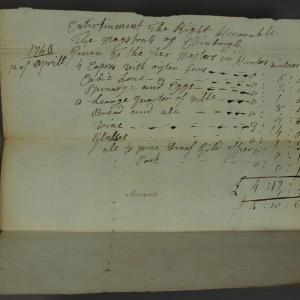

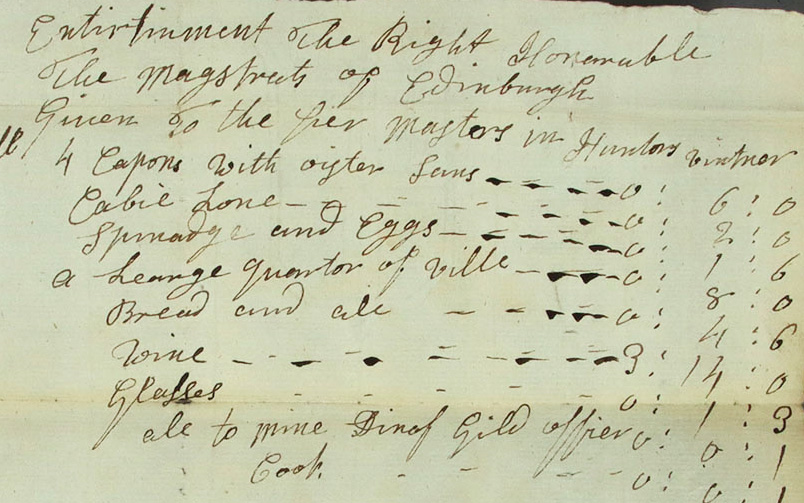

The bills are records of meetings of the Guild Court. This was an organisation bringing together the city’s merchants to oversee trade and markets, but they also carried out charitable work for the city’s poor. They were not catching up over a quick drink on the way home, but instead met for lengthy evenings to discuss such weighty matters as the management of the city workhouse, entertaining city magistrates or rewarding the fire brigade and notorious city guard with a pint and a roll. Many of the bills note who paid for the costs listed, or fees that were to be reimbursed from the Guild Court. The name William Butter appears a few times; he was treasurer to the Guild Court. We get the impression that these receipts were kept by individuals claiming expenses for wining and dining on official business.

Some to porter, some to punch

What strikes us the most about the bills are the detailed lists of food, drink and services enjoyed by the tavern customers. Comparing the prices paid can tell us a lot about the spending habits and tastes of the 1700s, as well as what counted as a fancy night out, or just a low key drink down the pub.

As you’d expect, alcoholic drinks feature prominently. The staple drink was ale, a beer made without the addition of hops. Most bills include 'bread and ale' served in much the same way we’d get bread and a jug of water today. You could normally get this for about a shilling. The next cheapest and common drinks were beer (made with hops, and lighter than ale), porter (a stronger and darker beer from London) and punch, a rum-based mix.

At the upmarket end, Claret is consistently the most expensive drink. This is a term for red wine from Bordeaux in France, a region which still produces some of the finest wines. One bill even makes a point of stating “6 bottles best claret”. Another bill hints at a good evening where no-one wanted to go home. After a meal of beef, tripe, coffee and port is a simple entry for “more wine”. Another bill goes further for the night of 30th July 1767 at Avalons in Leith where customers were charged 1 shilling for “broken glass”!

Not all drinks listed were alcoholic; one drinker in 1769 paid 2 shillings for “coffiei”, or coffee. At this time, coffee was drunk mainly in coffee houses rather than taverns. Would you go to a pub for your matcha latte?

Pub grub

If you were looking for a fine dining experience in 1760s Edinburgh, these taverns were not the place! Food served here seems cheap, simple and filling. Typical listed items are:

- Beef

- Lamb

- Tripe

- Spinach and eggs

- Salad

One spring morning in 1743, four gentlemen sat down to a serving of “capon with oyster sauce” (a capon is a chicken). At this time, oysters from the Forth were cheap and easy to get hold of, and did not carry the association with luxury and refinement they do now. An entire culture of oyster cellars grew up in the Old and New Towns where millions of oysters were eaten each year - that’s another story for another time!

How are you getting home?

Food and drink wasn’t all that could be bought at these taverns. Customers could be charged for a whole range of other services. Many bills list tavern staff such as servants, cooks and waitresses (listed simply as “girls”), but we also see listed some of the things that the diners needed at short notice (paper, coals for the fire and a candle). If a landlord/ landlady could not satisfy their customer's requests, they could always turn to Edinburgh’s army of caddies. These were mainly young men who were licensed by the city council to deliver messages and undertake all sorts of errands. They were the eyes and ears of the city, and eyewitness accounts from the time tell us that nothing happened without them knowing about it. They were relatively cheap (less than a shilling, or the same as the bread and ale) but one caddy booking in 1768 cost the same as four servings of roast chicken at 6 shillings. We can only wonder what mission this particular young man had been charged with.

Finally, every night out ends with finding our way home. But 18th century Edinburgh was not safe at night, despite the watchful eye of the caddies, or protection by the city guard. So taverns could call on various means to take people safely home. Horse drawn coaches could be hired, or perhaps a sedan chair carried by two porters if you needed to get into the narrow wynds of the Old Town. The streets around St Giles must have been throbbing with the clatter of horsehooves, calls of people hailing a coach or a caddy, and the shouts of those on foot wending their way home. I defy you to stand on the High Street late one Friday and tell me things have really changed that much!