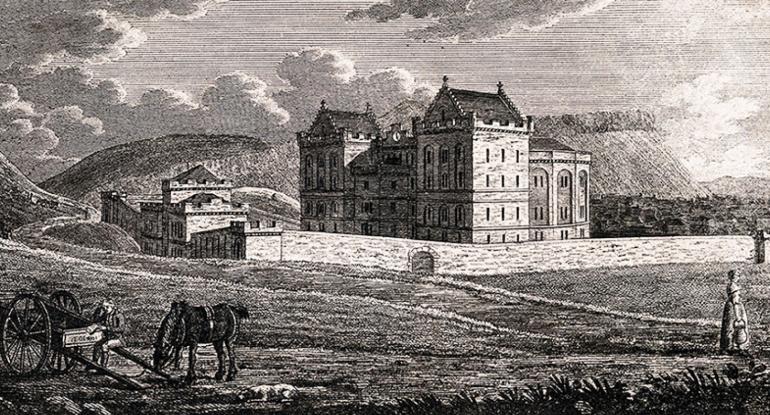

Our curators have been exploring the collections at Lauriston Castle and have discovered a small innocuous looking table that is placed beside the bay window in the Sitting Room. It always has a pair of binoculars on top of it. Perhaps Mr and Mrs Reid, Lauriston Castle’s last private owners used them for looking out to Cramond Island and the First of Forth. The table is very elegant with its long tapering legs and was made in about 1795. It was not of course made to hold binoculars. It is known as an urn table and has what looks like a drawer on one side but when opened it reveals a small shelf designed to hold a tea pot or teacup which would sit below the hot water or tea urn placed on the tabletop above it. But what makes this table more interesting is its links to colonialism.

In the 18th century sugar was a plantation crop produced by slave labour in the West Indies, while tea was imported from China. Tea has its own contentious colonial history, but it is the combination of tea and sugar in western culture in the 18th century that links it so strongly to slavery. Both tea and coffee were sweetened by sugar which made it palatable to western taste, and it was on sugar plantations where there were often the worst conditions and highest death rates amongst slave labourers. So inexorably were sugar, tea and slavery linked, that one part of the abolitionist campaign was to persuade people in the UK, particularly women, to stop taking sugar in their tea. Around 300,000 people boycotted sugar and sales dropped dramatically.

Yet it is not just what this table was used for which connects it to slavery and colonialism. Its connection lies within its very fabric – in the wood it was made from and the firm who made it. Mahogany became the must have wood of the 18th century and was prized for its exotic nature, its strength and its colour. Its extraction from virgin forests directly used slave labour while the mahogany trade was also tied into the wider context of slave trading via forest clearance for new plantations and through trade in the products of these plantations – products such as sugar, coffee and rum. Then there was the return trade of British and other European produced goods, including mahogany furniture to furnish the homes of plantation owners.

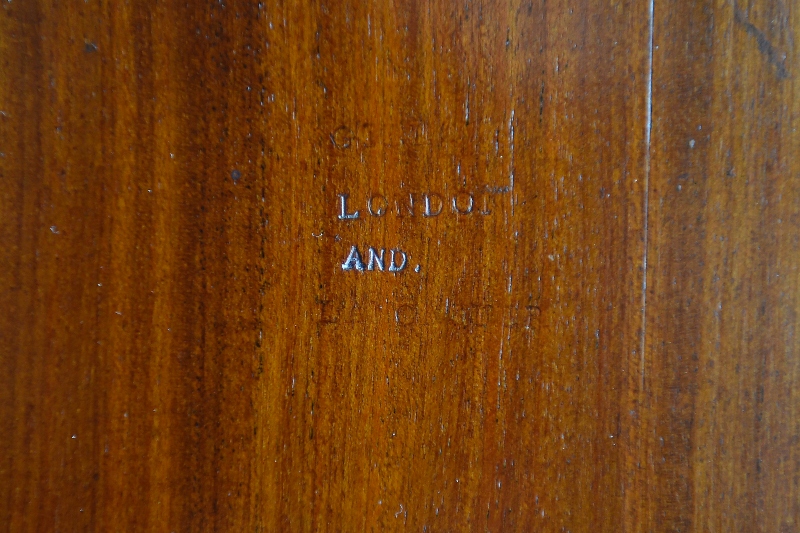

The Lauriston table is made from Mahogany and was made by the English Cabinet making firm of Gillows. The slide out flap for holding a cup or a teapot is stamped with their name. Founded in Lancaster in about 1730 by Robert Gillow, they also had a branch in London. The firm remained in family ownership until 1814 when it was taken over by Redmane, Whiteside and Fergusson, but it continued to trade under the Gillows name, before it merged with Warings of Liverpool in 1903. Today, few people would think of Lancaster as having stronger links to the slavery than the general prosperity that so many towns and cities accrued in 18th century Britain from the trade in slaves and slave produced goods. Yet at one stage during the 18th Century Lancaster, with its links to the coast via the river Lune, was the fourth largest slave trading port in England. Research by Imogen Tyler from Lancaster University has highlighted Lancaster’s role in slavery and the role played by the Gillows family.

Gillows were one of many Lancaster firms who participated in this trade. As makers of fine furniture Gillows would of course use mahogany and imported wood directly from the West Indies. But Gillows involvement in slavery went much deeper than this. As well as importing mahogany, they traded in rum and sugar and exported fine furniture in return. Through their investments and business connections they also directly traded in slaves. Their account books suggest that between 1754 and 1765 three quarters of the ships financed by Gillows were slave trading vessels. At least 40% of their profits in the mid-18th century came from the profits of directly trading in slaves, while the rest of their profits were linked to materials and products that had been created by slave labour.

Gillows were just one of many businesses in Lancaster that profited from the slave trade. Lancaster was a prosperous place and Gillows benefited from this wealth creation, making fine furniture and creating interior decoration schemes for landowners and middle-class businessmen in and around Lancaster, whilst their London branch opened up a wider clientele base beyond Lancashire and Northern England. One of their Lancaster clients was John Bond, who twice became Mayor of Lancaster. He inherited several plantations including over 700 slaves in what was then British Guiana from his uncle Thomas Bond who had also been a slave trader. Later, John Bond became a multi-millionaire from the Government scheme which compensated plantation owners for the loss of their human ‘property’. Some of his fortune was spent on buying fine furniture produced by Gillows for his various properties, including his town house in Lancaster. He became one of Gillows’ biggest clients and his son Edward later became a partner in the firm, although by then Gillows was no longer a family run business.

The Lauriston table was made in about 1795, so it dates from the period when the Gillow family were still very much involved in the furniture business they had built up during the 18th century. It also dates from before the abolition of the trade in slaves 1807, and well before the abolition of slavery in 1833. William Robert Reid ran a cabinetmaking business and collected fine furniture and we can assume he collected this as an example of the furniture Gillows produced, without thinking or knowing its deeper history.

It has so many links with slavery and colonialism – tea, coffee, sugar, mahogany and a firm actively profiting from slavery. A dreadful history for something that is really quite a beautiful and innocuous looking piece of furniture.