In this blog, Gwen Thomas, Collections Care Officer, gives an insight into how we look after the physical wellbeing of our collections.

Our museums and galleries look after a lot of different objects, from Paolozzi sculptures to Barbie dolls, 16th century documents to 21st century protest placards. But what does ‘looking after’ mean in practice? As Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s Collections Care Officer, my job is to physically care for everything in our collection, and to support my colleagues to do the same. Care could mean making sure objects are safely and securely displayed in our museums; packing each object in the most suitable way in our collections store; or making sure that an object’s environment isn’t causing it any damage. This blog focuses on how an object’s environment can impact upon it, and how we intervene to maintain our amazing collections.

Invisible factors like light, UV, incorrect temperatures and high or low humidities need to be managed to prevent mould and insect outbreaks among our collections. These invisible factors may also cause fading, cracking and sagging in objects. It’s important to manage the environment in order to preserve objects for the future.

There are also times when we have to offer hands-on care to our objects, for example if they are dirty, have been attacked by insects, or have water damage. If there is a bigger problem, like a broken part or flaking paint, we usually have external specialist conservators treat the object. For day-to-day care, Museums & Galleries Edinburgh staff and volunteers carry out the work.

Before embarking on any treatment, we will visually check the object all over and write up any damage or problems that we can see. This is called a condition report, and we will do these for objects that we borrow, like this loaned artwork by Ian Hamilton Finlay, as well as for our own collections as part of Auld Reekie Retold. This process helps us track issues over time and identify new problems.

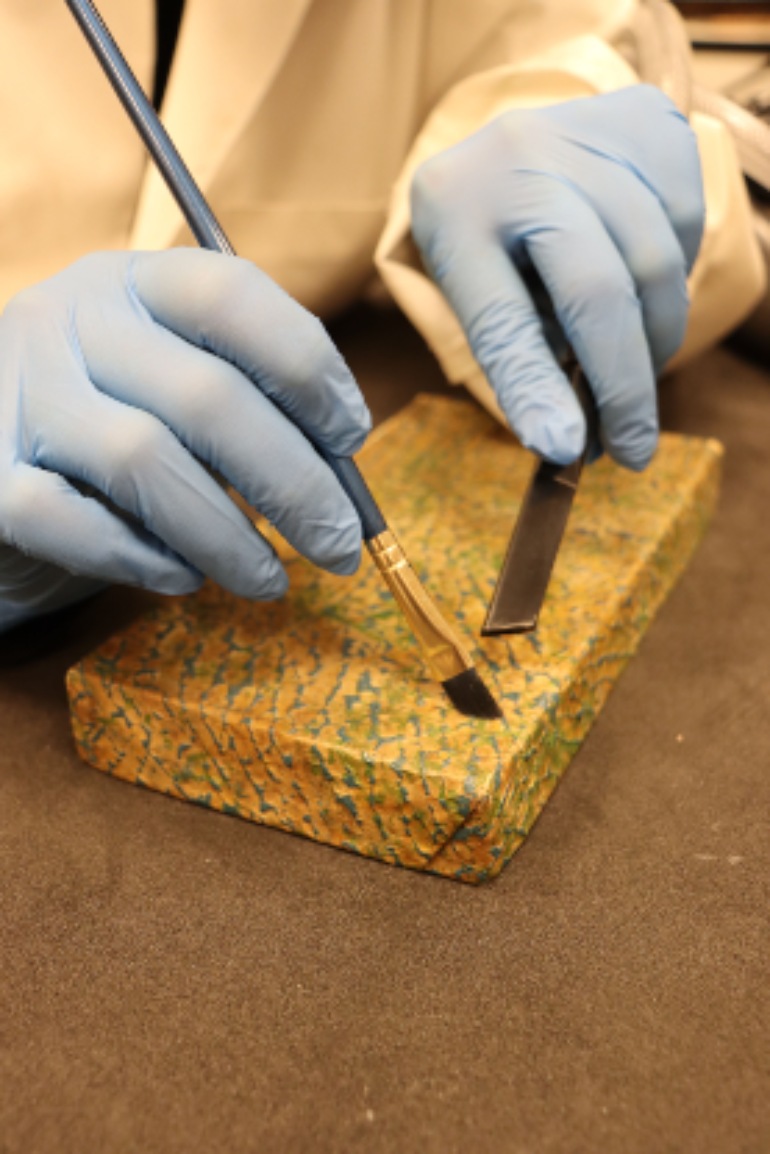

If an object is dusty or has other deposits on the surface, we will try to remove the dirt with a dry brush or a cloth first. If the object is fragile or made from an easily damaged material like silk or silver, we might use a soft brush made of pony hair, or smoke sponge, a rubber sponge which lifts dirt safely off delicate surfaces.

If possible – and it isn’t always, because all our museum buildings are historic and power sockets are never where you need them! – we try to brush dust directly into a vacuum cleaner with a small nozzle, so the dust is completely removed from the environment.

Sometimes when dirt has become very ingrained, or set into the surface of the object, we might have to use some water with a cotton wool swab to very gently remove it.

Water is never our first step, as it can cause more damage to an object than dust particles. If dirt or staining is really bad, we might consider using a solvent like white spirit or acetone. We will only use a chemical cleaning method, which includes water, if it is safe for the object. Acetone, for example, can cause plastics to melt, so we are unlikely to risk cleaning a plastic doll this way.

As well as dust, there are other reasons we might need to check, treat or clean objects. Mould, for example, can cause serious problems for a museum object, and is very difficult to permanently remove.

We have a lot of objects in our collection that are vulnerable to insect attack, such as carpet beetles or clothes moths – textiles, teddy bears, furniture and more. As we monitor for insect activity with sticky traps, we usually get an early warning if there are pests about. However, insect attacks can be quick and devastating.

When we learn that we might have an insect infestation, we check all the objects in the affected area thoroughly. We will clean them using a brush or smoke sponge to remove dust. If we find evidence of pest activity, like moth cases or frass (insect poo), we might freeze the object or treat it with a museum-grade pesticide, to eliminate the infestation. When objects are frozen, they are double wrapped and sealed in polythene, with some extra acid free tissue inside the package as a buffer. Depending on how cold the freezer temperature is, objects are frozen for between 48 hours and two weeks. We then let the objects defrost slowly before unpacking and checking them. We only freeze organic materials, like wool, silk and wood. Some things that are particularly fragile, or have very thin layers that could be split by the ice crystals, would not be frozen to avoid more damage.

Checking and cleaning museum objects isn’t always easy, because of how varied our collections are. A lot of things are in display cases, or out on open display at Lauriston Castle which can mean tiptoeing around inside without knocking anything over!

Working hands on with museum collections, and making sure they have the best environment and care possible, may be tricky and time consuming, but it is incredibly rewarding. Our care and attention means these objects will be around for future generations of museum visitors to enjoy.

You can see more items from our collection online on the Capital Collections website

You can find out more about how we store the objects in our collection on the Stories section of our website.

Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.