Auld Reekie Retold is a major three year project which connects objects, stories and people using Museums & Galleries Edinburgh’s collection of over 200,000 objects. Funded by the City of Edinburgh Council and Museums Galleries Scotland, the project brings together temporary Collections Assistants and permanent staff from across our venues. The Auld Reekie Retold team are recording and researching our objects, then showcasing their stories through online engagement with the public. We hope to spark conversations about our amazing collections and their hidden histories, gathering new insights for future exhibitions and events.

In this blog, Oliver, one of the project’s collections assistants, explores the story of Edinburgh’s theatres through its playbills.

How better to showcase Museums & Galleries Edinburgh collection of playbills than by sharing these online and putting them in the limelight?

Playbills were first produced in the mid-17th century and were simply a piece of paper with a cast list and other minor details of the play. Over time they developed, becoming more elaborate and richly decorated.

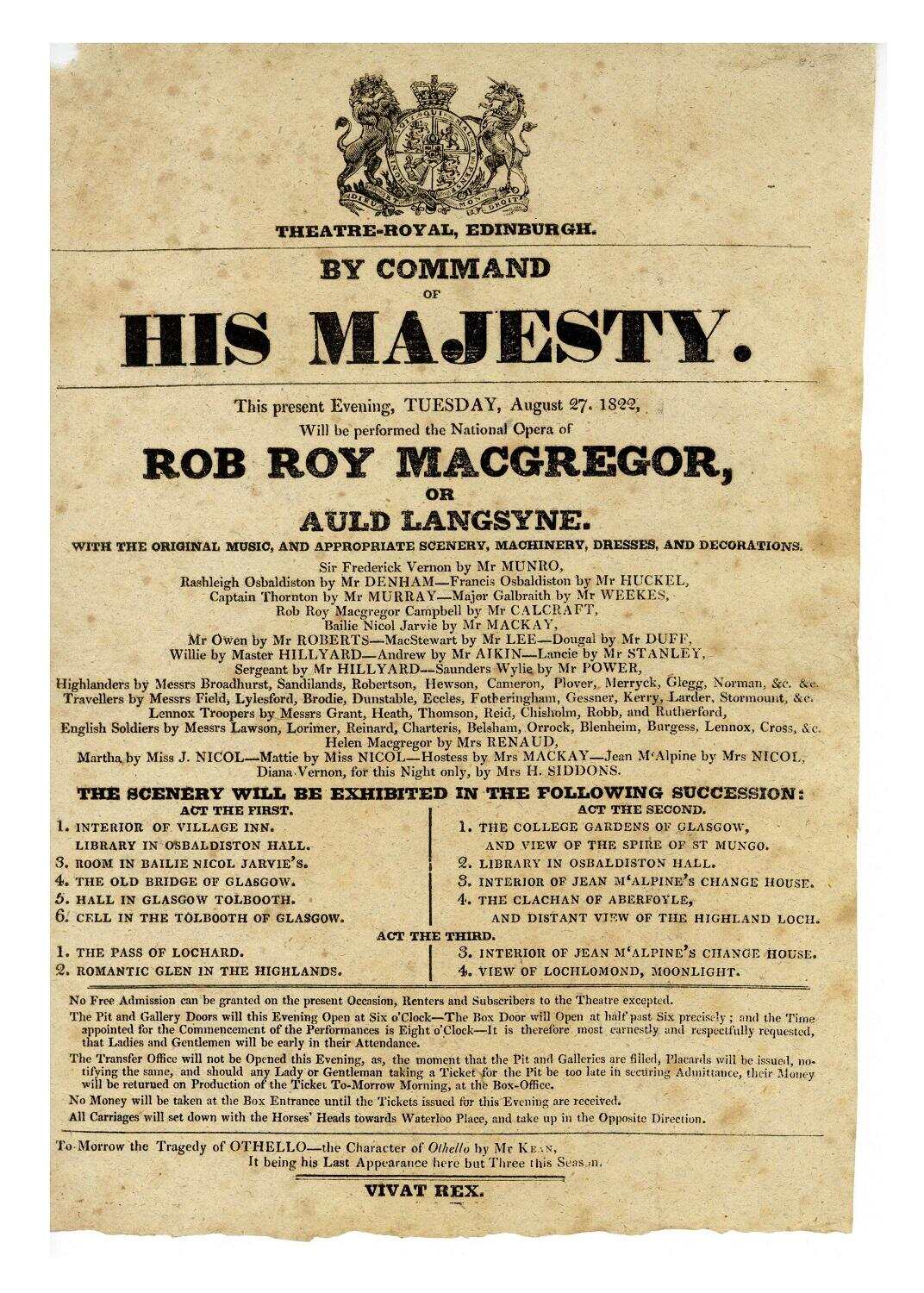

In the collection of the Museum of Edinburgh we have playbills going back to the early days of Edinburgh theatre. In 1822 King George IV visited Edinburgh amid much pageantry, orchestrated by Sir Walter Scott. As part of the celebrations, George IV demanded Scott’s famous work, Rob Roy, be performed. The performance was a roaring success and put Edinburgh theatre centre- stage. Our collection contains a playbill from this performance, which was recently on display at the National Museum of Scotland as part of the ‘Wild and Majestic: Romantic Visions of Scotland’ exhibition.

The playbill is a simple piece of paper that lists the name of the performance, the cast, the scenes and a short advertisement for the next performance at the theatre.

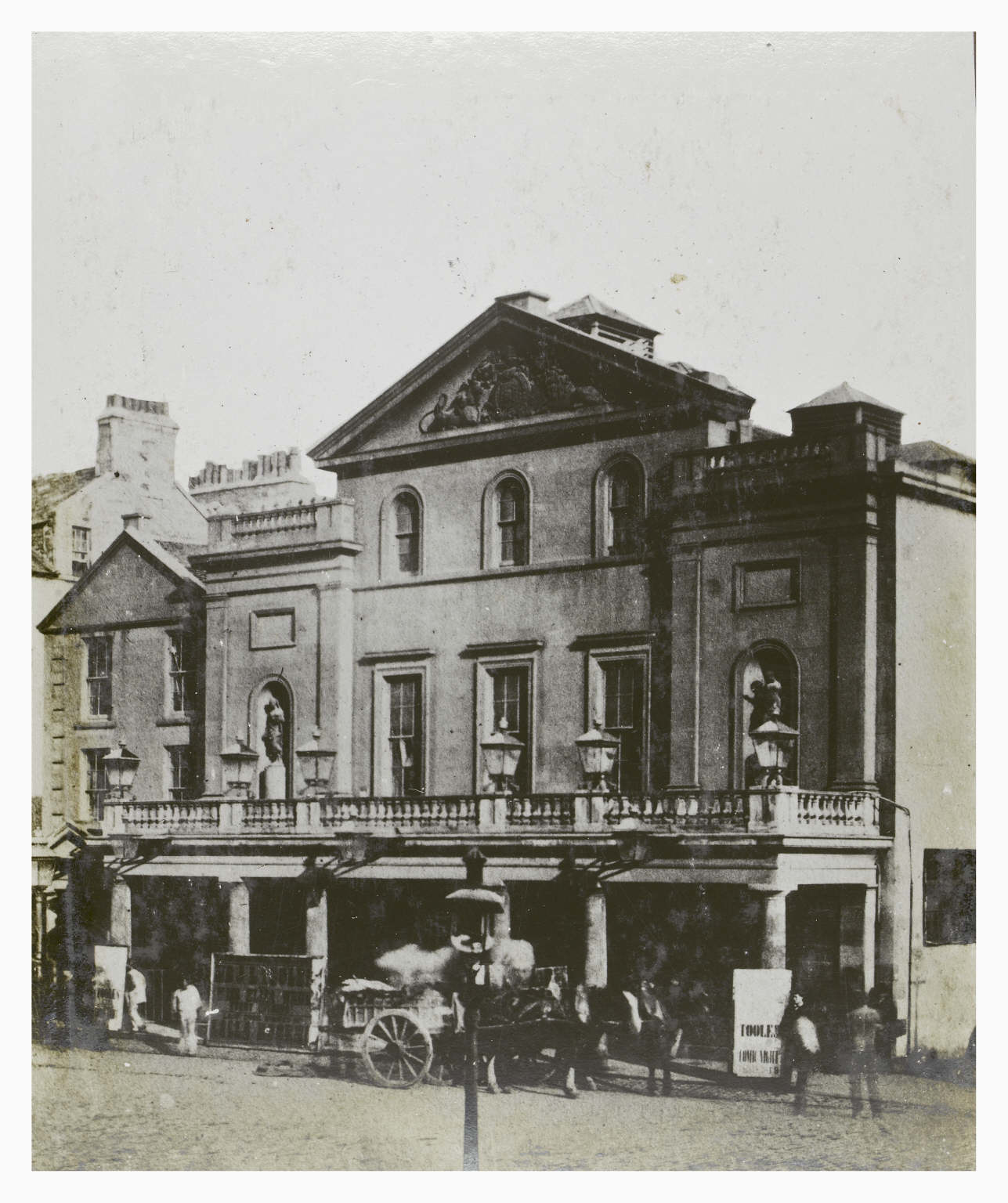

This performance was held in the Royal Theatre on a site in what was then known as Shakespeare Square. It is now the site of the Waverly Gate offices, at the corner of North Bridge and Waterloo Place.

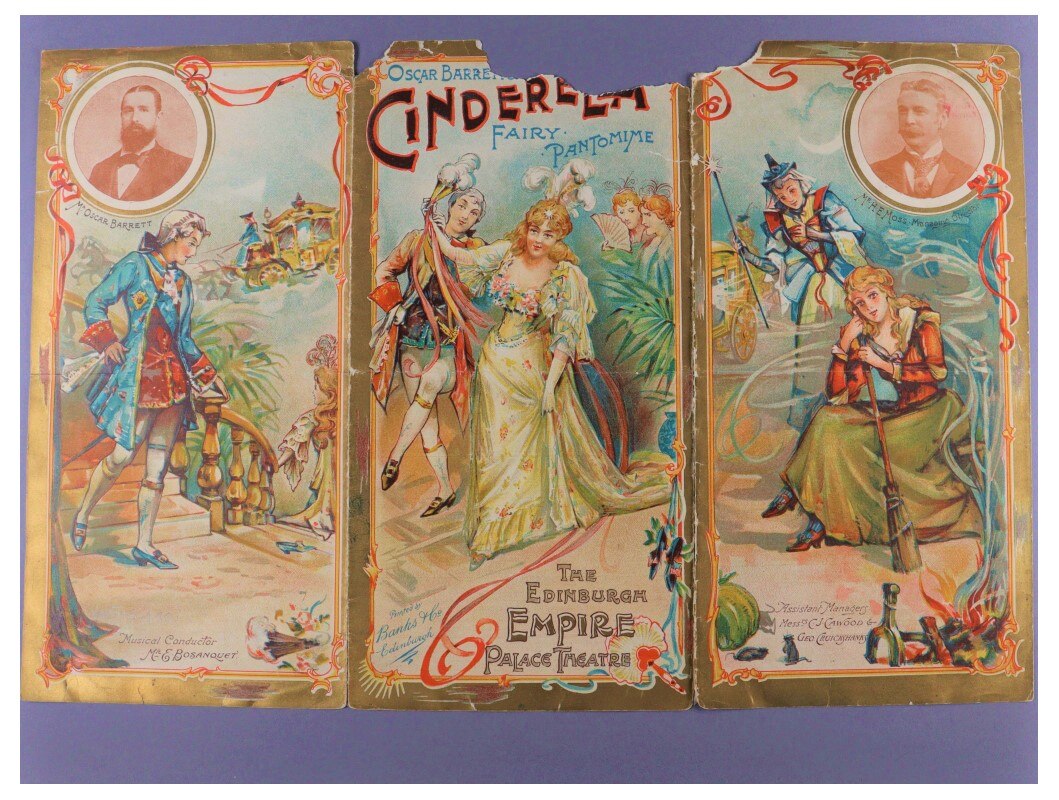

Over time, theatres sought ways to advertise their productions more vividly and produced more elaborate playbills to capture the public’s attention.

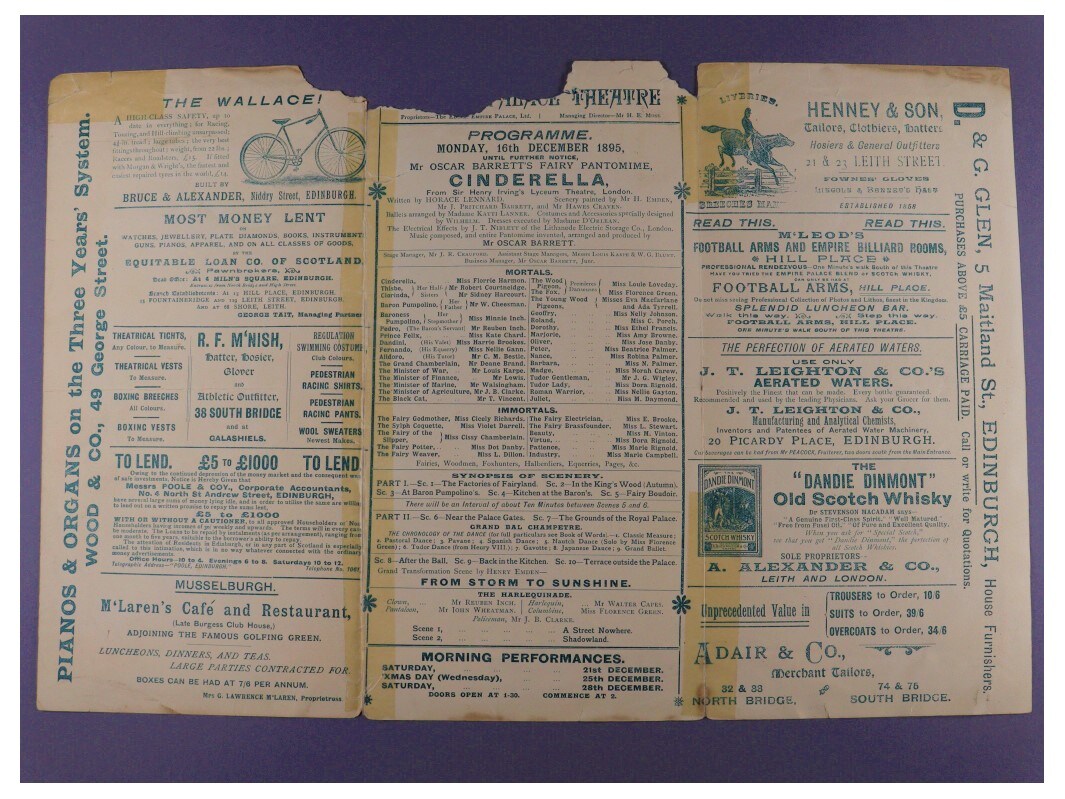

This play bill was for a pantomime performance of Cinderella in December 1895 at the Edinburgh Empire Palace Theatre, now the Festival Theatre. You can see that a lot has changed since the design of the play bill from 1822. The play bill has evolved into an object you would want to keep and even display. The design is eye- catching and inside contains a lot of extra information.

Only a small space has been given over to information about the performance - the rest is filled with advertisements for cafes and bicycles, such as the intriguingly named ‘Wallace’.

Edinburgh theatres sought other ways to attract attention. In 1925 the Edinburgh Lyceum Theatre made good use of German currency to promote their production of ‘Tons of Money’. They used the German ‘Mark’ as it was worthless and had more value as a play bill than a bank bill. Following the First World War, Germany had to pay enormous sums of money to the Allied nations, however Germany had no gold to back up their currency and so printed more and more bank notes to pay debts. As a result, the money became worthless.

The bank note/ play bill is in our collection. It is printed in the same way as any other bank note. However, on the right hand side the theatre company has printed its own advertisement in a blank space, ‘Tons of Money, The Laugh of the Century’.

This isn’t the most unusual thing that people did with the German Mark. Across Germany children were turning the currency into kites, paper chains and even confetti as the currency was worth next to nothing.

Museums & Galleries Edinburgh have a fantastic cast of items that tell exciting stories. See below for a link to more.

You can see more from our collection online at www.capitalcollections.org.uk